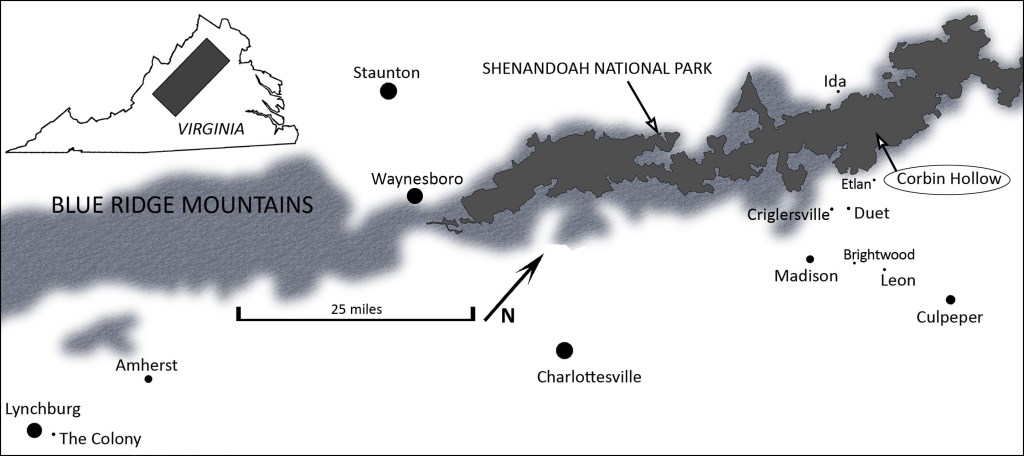

To hikers in Shenandoah National Park, Corbin Hollow is a procession of forested hillsides, copperheads, and collapsed chimneys. But the hollow is filled with ghosts.

In collaboration with documentary filmmaker Richard Robinson, I have just published an article in Southern Anthropologist that documents and tries to make sense of the drama that unfolded here — and in local hospitals and in the pages of newspapers and books. It’s a tragic tale but it’s a true one and also a relevant one to our world today. This is the expedited version of it.

You can think of it as a drama in three acts.

Corbin Hollow and the World

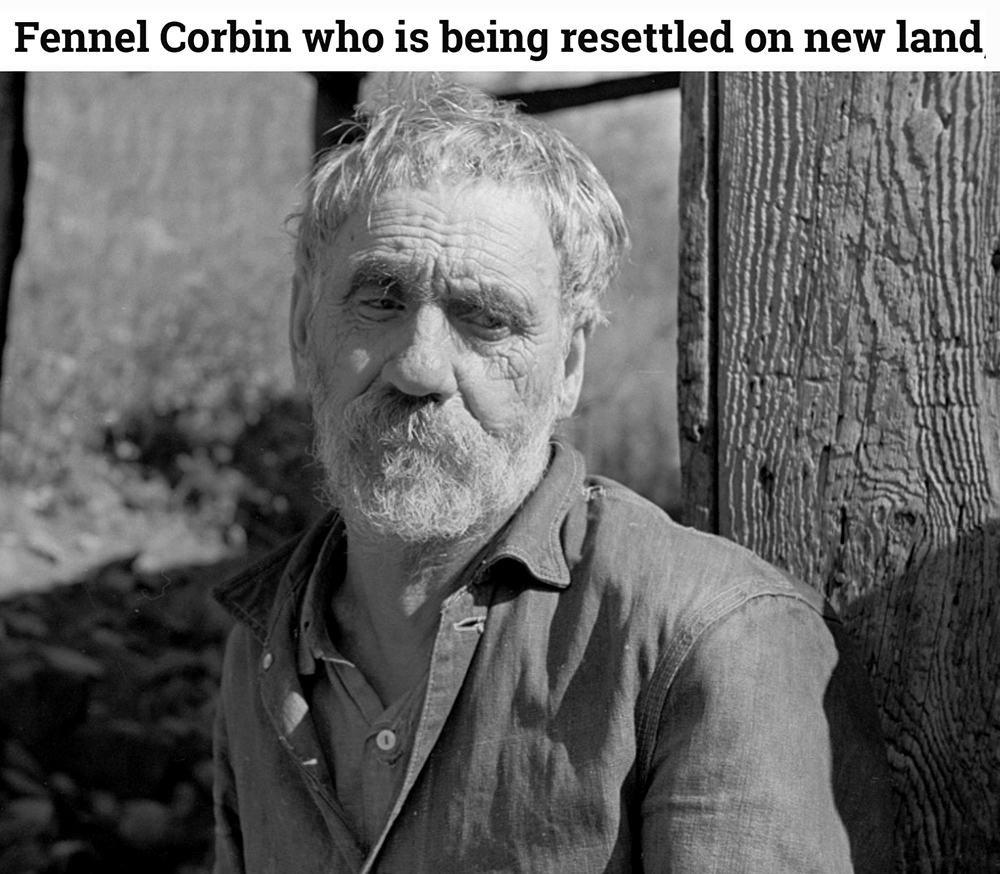

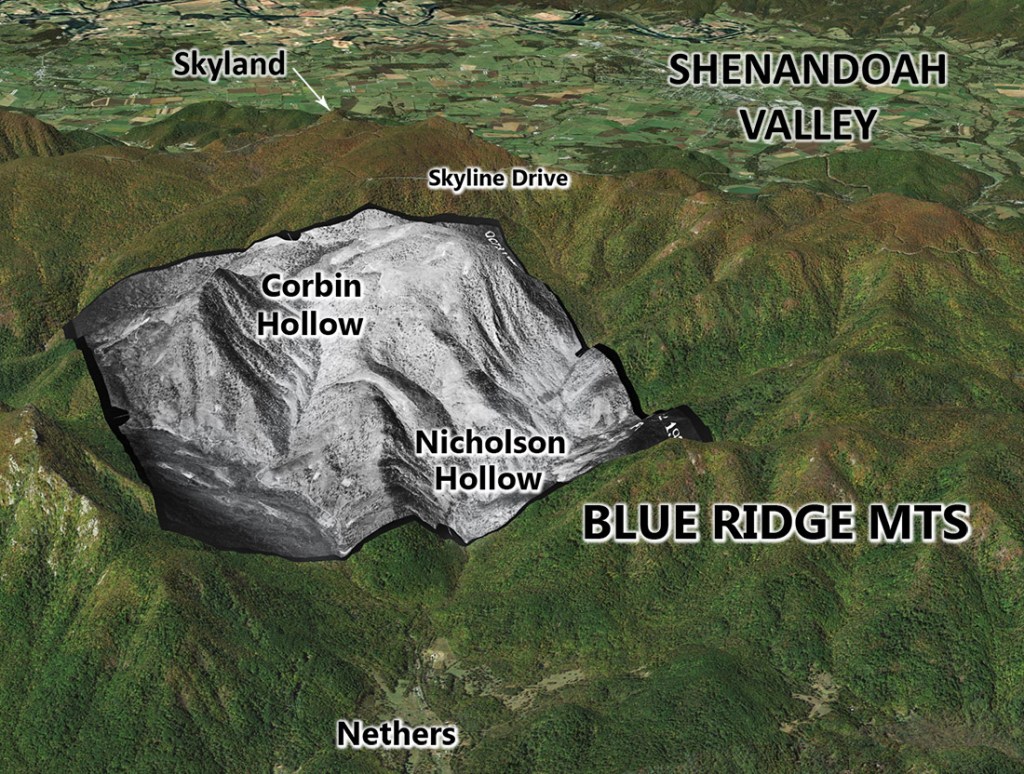

In the 1st act, there was a small community of unexceptional country folk living in a “holler” of the Blue Ridge Mountains. In 1816, Bluford Corbin, a War of 1812 veteran, bought land along Brokenback Run in the lower reaches of what is now called Corbin Hollow. In the 1890s his grandson, the colorful Fennel Corbin, moved into the steep-sided upper part of the hollow. Farming was harder here, but they got by with an economy combining local resources with some income from a new mountain resort called Skyland. The Corbin clan gradually grew.

Although quite poor by economic measures, mountain life was rich in many ways, and later on, even when life was falling apart for them, observers remarked on the happiness in the community.

The curtain rose on the 2nd act in 1928 when Virginia donated a large tract of Blue Ridge Mountain land to create Shenandoah National Park. This is called “condemning” the land, and to most of the 500+ families living there that’s exactly what it felt like; they had to give up their homes. In some areas residents were offered agreeable compensation, but not the Corbins: their holdings were of low value and some families lacked documents for land they had bought and were considered squatters. Fourteen families were basically stranded in their homes as the Depression set in and the local economy crashed around them.

Eventually they needed bags of food aid to stay alive.

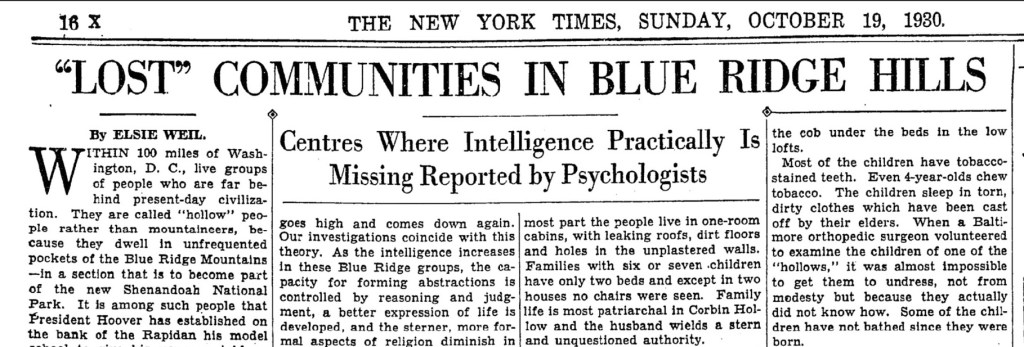

In this act they became celebrities. The national press seized on their shabby cabins and thick accents to spin lurid stories of poverty, isolation, and cultural backwardness. They were a described as Rip Van Winkle culture in a time warp just two hours from the nation’s capital, only recently “discovered” by a group of hikers. They had “no experience in farming” and their children had never tasted milk, played with toys, or heard of Santa Claus. They spoke a “queer Chaucerian English.”

And there was something seriously wrong with these folks. In this “lost community”, The New York Times explained, “intelligence practically is missing”. In 1933 the scientific monograph Hollow Folk pronounced the Corbins as exhibiting “the lowest level of social development”, apparently the result of that missing intelligence.

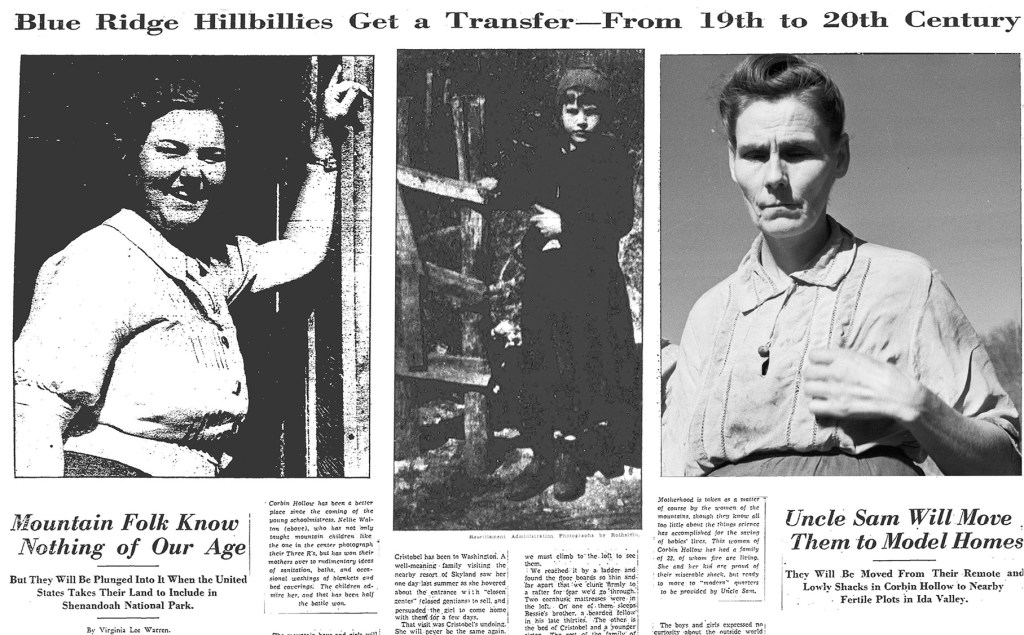

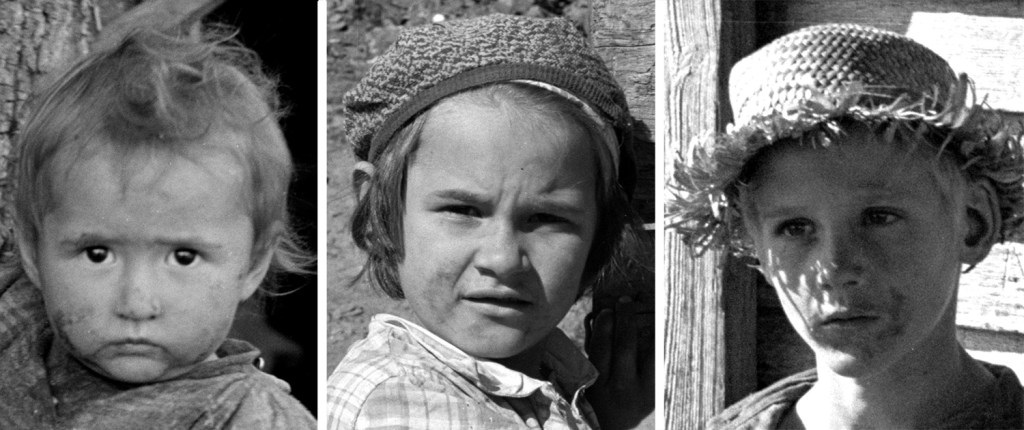

Government photojournalist Arthur Rothstein documented them as glum barefoot hicks with “half-wit children.”

This was all music to the ears of the eugenic scientists of the day, who held that “social inadequacy” resulted from bad genetic stock. “Paupers” were poor because they had “pauper genes.”

What could be done about this “leprous spot on the national body” (as the New York Times put it)?

Ah well most of the articles and photos celebrated how the Corbins would soon be resettled in modern houses in lowland — “transferred into the 20th Century”, said the Washington Post, when Uncle Sam moves them into “model homes”. Everyone seemed to agree this would be for the best. After all, as Secretary of the Interior Ray Wilbur assured readers, “they have nothing to lose”.

In the third act the Corbins’ story was retold from a more sympathetic perspective. By the 1940s eugenic science had fallen apart, exposed as not only scientifically bankrupt but conducive to atrocities. It turns out there aren’t “pauper genes” any more than — well, to quote anthropologist Jon Marks, any more than there are Irish “policeman genes” or Jewish “stand-up comedy genes.” And the whole “hillbilly” stereotype was reimagined. In a wildly popular 1962-1970 sitcom, The Beverly Hillbillies were presented as clean, amiable, and moral (although a bit oblivious); The Waltons (1972-1981) offered a warm view of family life in a village not far from Corbin Hollow; and the 1972 Foxfire Book — a catalog of mountain lore — was a best-seller.

And scholars looked more closely at the realities of life in Blue Ridge hollows. Archaeologist Audrey Horning combined archival research with excavations, and her book debunked the earlier claims of isolation: there had been radios, toys, and consumer items in Corbin Hollow. Actually, she wrote, the Corbins suffered more from “their involvement with the so-called outside world” than from isolation. They had become too dependent on income from Skyland and so were “wide open for disaster when the Depression struck”.

Historian Sara Gregg unpacked how mountain communities had managed (and been managed) throughout the New Deal. She pointed out that Corbin Hollow had been strained by population growth and devastating land cover changes, and was not economically and agriculturally viable for the long term.

Rhetoric scholar Katrina Powell, herself a Madison County native, used mountaineers’ own words in a moving look at their experiences of displacement. Filmmaker Richard Robinson produced an experimental documentary that explored the agenda in Corbin imagery that claimed “documentary truth”.

Other initiatives to document and honor the experience of the former hollow dwellers include the Blue Ridge Heritage Project, the Children of the Shenandoah, and JMU’s Shenandoah Oral History Project.

Theory of the Black Swan

Our new article uses extensive archival research to show that while Horning and Gregg were right, strictly speaking — the Corbins did end up with no safety net, and their lives did prove unviable in the end — there is much more to the story.

I don’t believe that life in the hollow was inherently unviable, overpopulated, or without safety nets. There are strong indications that their mountain adaptation should have gotten them through even tough times.

But what happened went far beyond tough times. Between the late 1920s and mid 1930s the Corbins suffered an unprecedented and unpredictable sequence of disasters. Some would say it was right out of the Book of Job, but a better metaphor is Nicholas Taleb’s concept of the Black Swan — an extremely impactful event that lies so far outside the realm of regular expectations that nothing in the past could have predicted it. But this Black Swan was not a single event, but rather an astonishing cascade economic, ecological, meteorological, legal, and medical setbacks.

Even then they might have gotten through with a little outside help — just like millions of others in the depths of the Depression. But the interventions that intended — or anyway claimed — to help the mountaineers’ didn’t. They destroyed them.

It’s a story worth hearing because, although it might seem like a whole different world than what we live in today, I’m not sure it was.

Pre-Disaster Hollow Life

People like the Corbins — rural cultivators with one foot in the market economy (selling some, working some for wages) and one foot out (subsistence farmers) are called peasants.1 And keeping that one foot out is a key to sustainability. Market economies can be fickle and merciless, and locally managed nonmarket systems can provide crucial safety nets like being able to grow your own food, make your own tools, mobilize farm labor without cash, borrow essential resources, and make time to help each other.2

There are no detailed accounts of life in Corbin Hollow before the late 1920s but there are sources that give us a reasonable picture of a local economy with some balance between market and nonmarket.

Their market economy had a bundle of minor income sources. Skyland provided wage work for carpentry, cleaning, cutting wood, and making hiking paths. It provided a market for forest products, flowers, milk, butter, moonshine, and especially baskets, a Corbin specialty (which they also traded for provisions at the country store in Nethers). A man from another hollow later recounted “seeing them Corbins carrying so many baskets they looked like a turtle.” At times income came from sales of chestnut and bark to tanning mills in the valley below.

Out of the market, subsistence came from fishing, hunting and trapping. Plant resources included chestnuts which fed both humans and livestock. Hogs ran in the forest until being captured for slaughter; a survey recorded four Corbin households owning pigs even after things were falling apart for them. They had gardens, cultivated fields of corn, and orchards, all of which provided storable foods: cabbage was buried in the ground to last all year, apples were dried and stored.

So although they were materially very poor, the indications are that into the 1920s the Corbins had an economic balance and safeguards against adversity. But what was in store for them was an unprecedented cascade of hazards that would shred their safety nets, break apart their close-knit community, and then “plunge them into a modern era” that had its knives out — literally — for people like them.

Things Fall Apart

The trouble started in the mid 1920s when the chestnut blight killed off the most useful trees in the forests. The loss of chestnuts hurt the food supply not only for humans and hogs but for hunted wildlife; it also clobbered the income from selling nuts and bark. A Post article cited the closure of a local tanning company as Corbin Hollow’s “first industrial blow”. So Corbin households were already struggling when the Park Condemnation Act put them on notice that they had to leave their homes.

But contrary to the rosy headlines, they had nowhere to go, and anyway no means to go there — their average cash settlement was only $570 (for comparison, the average settlement in adjacent Nicholson Hollow was $1323).

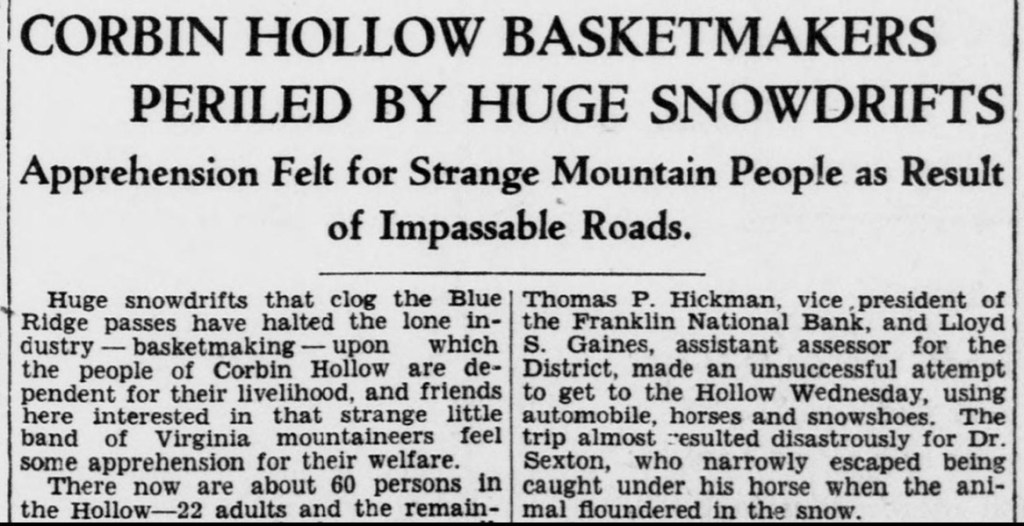

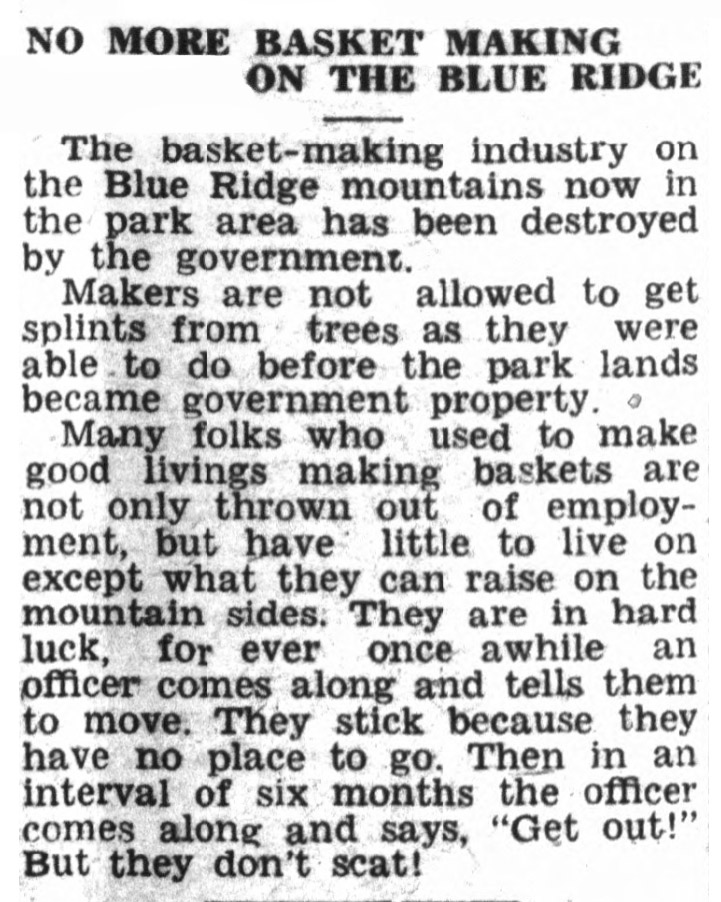

By 1930, with the Depression suddenly in full swing, Skyland patronage plummeted and so did income from wages and sales. Most basket sales dried up, even with the local Red Cross steeping in to help the Corbins find buyers.

Then, with their cash economy savaged by the Depression and their subsistence economy by the chestnut blight, came an extraordinary turn in the weather. The drought of 1930 dried up mountain springs and led to a 70% drop in corn yields statewide.

In 1932, Spring brought 10 foot high snowdrifts and then Summer brought another serious drought.

With their food stores already low, the staple crops of cabbage and potatoes failed across Corbin Hollow.

In December the Washington Post reported that “hog pens and chicken houses…[were] emptied by forced sale to recoup drought losses.” The shortage of livestock, cited in Hollow Folk as evidence of the “lowest level of social development”, was the result of the compounding effects of the recent cascade of events.

Intensifying cultivation on cornfields — fertilizing, irrigating, increased weeding — was difficult in the hollow. As in most of mountainous Appalachia, fallow-based (“slash & burn”) methods worked best. Even plowing was a problem, as most fields were too steep for animal traction. But they turned to human traction: one report described how “one man usually guides the plow while two pull it,” and that “Uncle Fennel made an especially built man-plow”. But cornfields there would never be highly productive.

Then the already deteriorating conditions got much worse as park officials began to tightly regulate the activities of families remaining in the park area. Hunting was banned; so was baskets making. When children from the hollows tried to sell flowers on the new Skyline Drive, parents were ordered to keep them home.

By the time the Corbins were finally forced out of their homes in 1937, they — like many millions of Americans — were unable to get by without food aid, which came in the form of bags of wheat flour and cornmeal.

And then the Corbins, the anti-hero celebrities of lurid accounts in nationwide press, disappeared from the media.

But not from the archives. The dusty pages in county courthouses and online sources reveal that the worst was yet to come for the Corbins — ironically, from humanitarian interventions.

We’ve Got Your Back

The three major humanitarian interventions available intended — or claimed — to benefit the mountaineers were A) food aid in the form of flour and cornmeal, B) sexual sterilization supposed to prevent unsupportable children, and C) resettlement into modern homes. But each of these interventions contributed to the community being essentially destroyed.

A) Food aid came to Corbin Hollow from some private sources (including U.S. President Herbert Hoover, whose mountain retreat was only 10 miles from Corbin Hollow) and from government relief. Almost all of the donated food was wheat flour or cornmeal. But the specifics of the grain in the bags of food aid were crucial.

Parts of the US South had been reeling from an epidemic of pellagra since the turn of the century. Pellagra is a serious malady that manifests as the “three D’s” of dementia, dermatitis (usually bilateral and symmetric), and diarrhea; untreated it can culminate in the fourth D of death. Its cause was a shortage of niacin (vitamin B₃), but for years its etiology was contested. A 1915 experiment showed the disease resulted from a heavily corn-based diet typical of the Southern poor and was cured by a balanced diet, but this was hotly dismissed by Southern leaders (who resented the blaming of their foodways), by anti-Semites (who scorned the dietary explanation as “Jewish science”), and by eugenicists (who attributed physical and behavioral abnormalities to heredity).

Eugenicists took particular interest in pellagra because its psychiatric symptoms were easily construed as “feeble-mindedness.” The suppression of the science on pellagra led to tens of thousands of deaths, and has been called the medical fraud of the century.

A dietary precursor of niacin is the amino acid tryptophan which would have been present in meat, fish, eggs, and other items in the Corbin Hollow diet in normal times. But not in the donated flour and cornmeal, thanks to “advances” in food processing technology. Corn has some tryptophan in the germ that can be made bioavailable by making it into hominy, but thanks to the Beall degerminator (in use after 1900) the cornmeal in the food aid sacks had none.

Whole wheat also has some tryptophan, but not the refined wheat from roller mills that came along in the early 20th century.

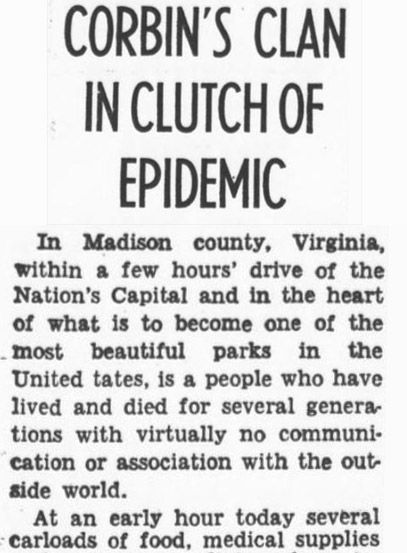

In August 1935 newspapers reported an epidemic raging through Corbin Hollow without naming the disease. It was pellagra — look at the symmetrical dermatitis in Rothstein’s photographs of Corbin children. The “impetigo” that a teen-aged Corbin girl was noted to have (in the eugenic sterilization case discussed below) was surely pellagra dermatitis.

There is no record that the health status of the Corbins was ever diagnosed or even considered, although the disease was well known.

The pellagra would do more than sicken the Corbins: it would make them especially vulnerable to the hazard of the second “safety net” — eugenics.

B) Eugenics. The Washington Post celebrated the Corbins’ transfer “to the 20th Century”, but the transfer was specifically to 1930s Virginia, which was in the grip of eugenic theory and forced sterilizations of the poor. In fact the notorious court case that confirmed the national legality of forced sterilizations had been argued just down the road in Amherst a few years before. And as offensive as it seems today, forced sterilization was conceived as a safety net. The law stated that if sterilized, “defective persons” would “become self-supporting with benefit both to themselves and to society” instead of having unsupportable children who were “a menace.”

The Sterilization Law came from “The Colony” — the Virginia State Colony for Epileptics and Feeble-Minded — in Amherst County. Its superintendent had been busily sterilizing lower-class women until he was sued in 1918. The Colony then had its lawyer craft a state law to indemnify physicians performing eugenic sterilizations. To ease passage, it explicitly recognized “both the health of the individual patient and the welfare of society.” It passed in 1924 and The Colony quickly set up a test case to make sure it would hold up in court. This was the Buck v. Bell case, in which lawyers went out of their way to establish — albeit through distorted and perjured testimony — that sterilization would be in Carrie Buck’s own interests. Carrie’s lawyer was a treacherous sleazebag and eugenics supporter who made sure she lost at every level up to the Supreme Court.

Most sterilizations took place in an asylum where people were committed after being designated as “defective” or “socially inadequate.” These were highly subjective labels, and many people in a position to make determinations saw poverty as prima facie evidence of social inadequacy.

There was also a racist motivation at work here: Black folk were sterilized too, but there was particular zeal for sterilizing poor and/or misbehaving White folks who challenged the myths of White superiority. It was race hygiene, and Virginia’s law inspired the Nazis’ 1934 sterilization law. (That year Dr. DeJarnette, head of Western State Hospital, whined that “the Germans are beating us at our own game”.)

So the overwhelming majority of those sterilized were poor, and mountaineers — stereotyped as untamed and backward — were especially vulnerable. Years later, a county supervisor recalled the sheriff’s men driving into the mountains to conduct “sweeps” in which they “loaded all of them in a couple of cars and ran them down to …sterilize them…Everyone who was drawing welfare then was scared they were going to have it done on them…[t]hey were hiding all through these mountains”.

So the Corbins would have been a target for the eugenics apparatus anyway. But now many of them were surely exhibiting dementia — which normally appears before the dermatitis we see in the photos. Pellagra dementia may include irritability, poor concentration, anxiety, delusions, apathy, confusion, and memory loss.

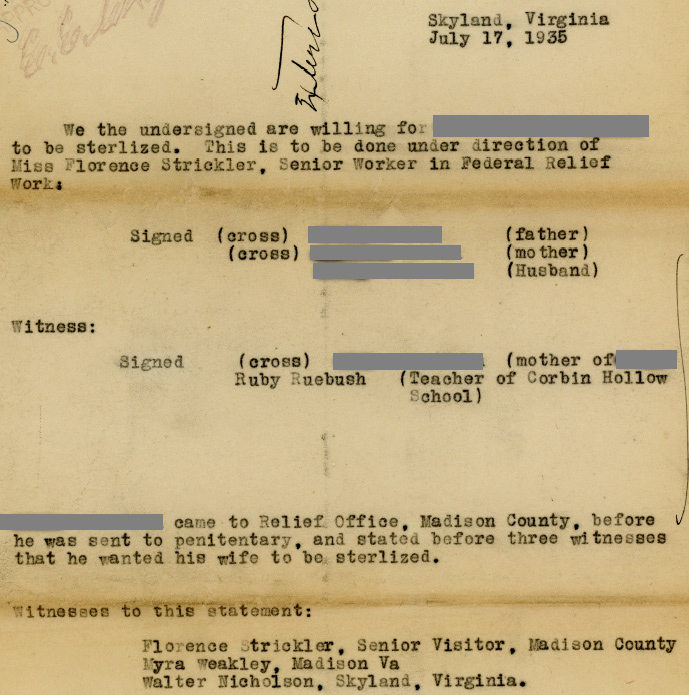

The process of sterilizing Corbins was underway before they were evicted from the hollow. The image of a Corbin woman in the Post article (above) was cropped from a photo showing her beside her 17-year-old daughter, who had recently married a young man from another hollow. A few months before the photo was taken, the social worker Florence Strickler had started the paperwork for the girl’s commitment and sterilization, obtaining “X” marks on approval forms from the girl’s illiterate parents and husband — who certainly had not really intended that the new bride would be rendered sterile.

Then just before the article was published, she was committed to The Colony, the papers citing “peculiar acts & speech”, headaches, and nervousness. She was also stated to suffer from “impetigo” which was surely pellagra dermatitis. After her salpingectomy, she was kept at The Colony for almost five years, then discharged as “Improved.”

Justifications for sterilizing other Corbin children include “silly conduct”, “tantrums”, and “incessant talker.” A particularly sad case was the 14-year-old boy from a neighboring hollow who was left homeless after his mother died and his father abandoned him. This left him “backward, stubborn, antagonistic” — enough to be committed and sterilized.

Colony records list 11 of the Corbins as committed and sterilized. Most were minors. It is also highly likely that other Corbin children were sterilized at outpatient clinics, but records are scattered and incomplete. Surely over half of the 25 children and young adults expelled from Corbin Hollow were sterilized.

C) Resettlement. The expulsion of the Corbins from their homes was presented as an act of good will. Newspapers insisted they would be “better located” and would “get a break” when “a great deal” was “provided by Uncle Sam.”

Actually most evacuees, even those much better off than the Corbins, bitterly opposed their expulsion. Famous examples were Robert Via, who fought his eviction up to the Supreme Court, and Mel Cliser, who literally dug in his heels when he was dragged away, handcuffed and singing the national anthem. To tamp down public outcry, park promoters steered attention towards the struggling Corbins, who reporters found to be easy fodder for snide copy — or imagery, in the case of photographer Rothstein. (This is what Richard Robinson explores in the documentary Rothstein’s First Assignment.)

The fact that life was falling apart for the Corbins because of recent historic events was obscured by the descriptions of a backward cultural isolate untouched by time.

But few if any of the Corbins would ever up in those “model homes.” Evicted families who couldn’t afford to buy new homes could get into resettlement homesteads only through government loans, and only those who passed interviews. And even then, they would be evicted again if they failed on their mortgage payments.

Given the pittance they got for their land, the Corbins would have been desperate to find places to live. And as a result, their community, which had been close-knit (for which they were ridiculed), was broken up and permanently scattered. The fragmentary paper trail shows that individuals wound up in Madison, Duet, Leon, Etlan, Brightwood, Waynesboro, Lynchburg, on Poor House road near Criglersville – and of course at The Colony in Amherst County, where many were committed.

Some of those sent to The Colony never rejoined their families. With incarceration periods ranging up to eight years, some Corbins decided that they had nothing to return to, choosing instead to live with other former residents of The Colony.

For patriarch Fennel Corbin, there would be no further family life. He was not to be “resettled on new land”, “moved into a model home”, or given “a great deal” by Uncle Sam.

He was finally evicted in early 1937. That April an article in the Luray newspaper quoted a letter supposedly dictated by Fennel from an “old folks home” in Waynesboro where he was “spending the closing days of his life.” In the letter, which bears no resemblance whatsoever to how he actually would have spoken, Fennel supposedly says that he is well treated, but that he “longs for the roar and swish of Broken Back River… as it swirled and snarled by my cabin’s door”.

In 1940 he was committed to Western State Hospital in Staunton, where he died in 1945 and was buried in an unmarked grave.

With Friends Like These

As the supposed safety nets devastated a community already reeling from ecological and economic blows, no one called serious attention to the physical and social violence these people were enduring. On the contrary, every category of professionals that was — or should have been — charged with helping the Corbins actually worked against their interests.

Especially Mandel Sherman, the lead author of Hollow Folk. He was an eminent child psychologist and University of Chicago professor, writing on the mentality and levels of cultural evolution. Social scientists are supposed to tell people’s stories and contribute to wider understanding of cultural differences. In my own tribe of cultural anthropologists we particularly value trying to see the world through other people’s eyes. But Hollow Folk was a cringe-worthy smear job based on shallow knowledge of recent life in the hollow. Remarkably, the book had a glowing preface by Fay-Cooper Cole, chairman of the renowned anthropology department at the University of Chicago, and a former student of the legendary Franz Boas who established the anthropological practice of actually living with your subjects before you write about them.

This shitty book echoed themes from the even shittier book Mongrel Virginians — a steaming pile of hearsay and innuendo about Monacan Indians in Amherst County, decorated with charts to make it look scientific. That eugenic-inspired treatise described shabby houses to make the occupants seem “socially inadequate” and good candidates for sterilization.

The journalists also have a lot of ‘splainin’ to do. Dozens of articles on the Corbins appeared between 1929-1936 — in the New York Times, Washington Post, Takoma Park Sligonian, the Associated Press, and papers in Montana and Arizona. Coverage was most extensive in the Washington (D.C.) Evening Star, where science journalist Thomas R. Henry — who also co-authored Hollow Folk — regaled readers with garish images of kids chewing tobacco and adults hearing a fairy tale and “spitting out their cuds in their growing excitement”.

No journalist made more than a shallow attempt to explain the Corbins’ economic problems, and none questioned the government’s rosy spin on the forced resettlement. Headlines cited “gift homes” even in articles mentioning that the houses were not gifts at all. The Post article at least included a touch of skepticism about “vague” government promises, but it also recycled caricatures from Hollow Folk and repeated the claim that the Corbins would be moved to “model homes.”

In the decades that followed, not a single journalist – even Henry —investigated what actually happened to these people.

And let us not forget Florence Strickler, the Senior Worker in Federal Relief Work charged with working with the displaced. Her time with FERA and Madison’s Social Services coincided with a surge in sterilizations, and it was she who signed most petitions for commitment. One can only imagine the line of bullshit she fed to the powerless parents and husband of the girl in the sterilization form above — and of course that girl was only one of many.

Never Again…?

A hallmark of Taleb’s Black Swan is that even though it’s an unpredictable outlier, we tend to look back and explain it as something we should have seen coming. This is called “hindsight bias”: the tendency, once we know the outcome, to overestimate our ability to have predicted it, and to reinterpret past evidence to fit the known result. The nuanced analyses by Audrey Horning and Sara Gregg mention the combination of setbacks, but we are still left with the impression that the hollow’s economy was inherently vulnerable and unsustainable.

No one knows how long that community would have stayed afloat without the tragic and unpredictable cascade, but the Corbins did have internal safety nets and some of the balance of a normally sustainable peasant economy. But they suffered a barrage of setbacks that decimated virtually all of their multiple sources of external income as well as most of their self-controlled resource base.

Even then, they probably would have come through if they’d only had a little help. Governments bail out communities, companies, whole industries, and individuals in acute trouble all the time. Getting people back on their feet was the main concern of the federal government for the whole decade of the 1930s. Instead, the government, while claiming the best of intensions,

- brought food aid that made them sick. (Well intentioned…but science knew that grain would make them sick.)

- took their kids away and sterilized them. (By a law that claimed, with a straight face, to protect them.)

- evicted them, gave them nowhere to go, and incarcerated their patriarch. (They were “transferred to the 20th century” alright – just a terrible part of it to be disempowered.)

It all gives new meaning to Audrey Horning’s comment that the tragedy of Corbin Hollow came not from its isolation but from its involvement with the “so-called outside world.”

At least this chapter is far behind us. Surely we will never again find ourselves in a country where health services are run by deranged quacks, innocent bodies are brutalized by state agents, and marginalized families are evicted and scattered like dry leaves.

Right?

Notes

1.The term "peasant" is sometimes used as a slur but not by researchers like me. In fact the top journal dedicated to these people is the Journal of Peasant Studies.

2. For more on this point see van der Ploeg 2008 The New Peasantries: Struggles for Autonomy and Sustainability in an Era of Empire and Globalization and Stone 2022 The Agricultural Dilemma: How Not to Feed the World.

Incredible story and you are right to draw a parallel with the US today.

Trump: immigrants and their criminal genes. Holy 1930s Batman.