Hard to imagine an odder way to start the day than sympathizing with Robert F. Kennedy Jr., but that’s what happened as I read about his “war on corn syrup.”

Corn processors’ defense of High Fructose Corn Syrup (HCFS) — “sugar is sugar” — may be partly true from a strictly nutritional standpoint, but cane sugar and HFCS have very different deep histories that RFK (and you, gentle reader) should know about.

The deep history of cane sugar is told in one of the truly wonderful books from my field of anthropology, Sidney Mintz’s Sweetness and Power. It’s easy to assume that the world consumes so much sugar simply because of the human sweet tooth, but Mintz shows that the real driver has not been taste buds but slavery. Before the 1600s, sugar was not a basic ingredient or even a spice – it was rare and valuable stuff made into fancy treats for the rich and the royal. But the 1600s brought the ramping up of the slave trade, and a new class of wheeler-dealers who had an embarrassment of riches in the form of coerced human labor. So much of it, in fact, that they – in collusion with European powers – invented a whole new form of production: the factory farm. Well the proto-factory farm anyway. Sugar cane could be grown and processed very intensively with copious amounts of unskilled slave labor on Europe’s scattered “sugar colonies.”

The problem of how to profit from all the slave-produced sugar led to vast increases in rum production, and to growing trade in bitter things made better by a spoonful of sugar – chocolate, coffee and tea. By the 1800s, factory owners in England found that giving exhausted workers an afternoon tea break for a hit of calories and caffeine squeezed more work out of them – hence “tea time”.

For European powers, sugar colonies were just the start; their economies grew by sucking resources out of colonies as raw inputs into those factories where tea-drinking workers made cloth from cotton, chocolate from cacao, furniture from lumber, and so on. And their populace ate grains and meat from their colonies, produced by coerced “colonial subjects.”

But the US, lacking colonies, followed a very different macro strategy: the integration of manufacturing with agriculture1. This came into full flower in the 20th Century as waves of government subsidy underwrote agricultural industry after industry – fertilizer, hybrid seeds, tractors, pesticides, GM crops, and so on.

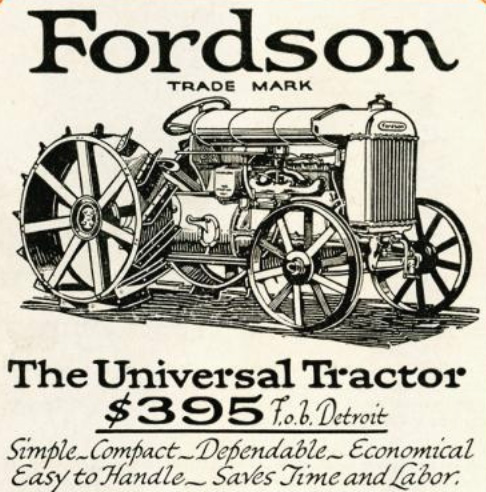

Old Henry Ford started selling tractors just a few years after the Model T came out. Of course today farms are much bigger so they all need tractors, but not in the early 1900s. Actually many farmers were coerced into buying them. The new breed of “agricultural engineers” at state universities pushed them, and banks preferred to make loans to tractor owners. Great book on this: Every Farm a Factory.

The reason America’s industrialization of agriculture is a big deal economically is that each agricultural input industry supports secondary and tertiary industries. The fertilizer industry supports factory builders, chemical companies, gas pipeline and fracking companies, trucking and shipping companies; the tractor industry supports steel producers, fuel companies, tire and rubber industries, engineers, computer makers, and so on. The high cost of running an American industrial farm – where a tractor alone can easily run $150,000 – requires credit, which supports the banking industry. Input industries also support research universities, where scientists develop more technologies, economists study the technologies’ benefits, and the occasional anthropologist writes about the whole system.

Most of the economic activity being funneled onto farms is indirect, so it’s impossible to arrive at a good estimate of the collective value of the enterprise, but the USDA reports that in direct costs alone (that is, excluding all that money circulating through secondary industries) American farmers these days spend $22 billion on fertilizer, $12 billion on fuel, $22.2 billion on seeds, $12.6 billion on tractors and other self-propelled farm machines, and $9.9 billion on interest. Almost all of this money flows OUT of the communities where the farms are and into the pockets of shareholders of Shell, Bayer/Monsanto, John Deere, etc.

The government keeps the whole system going by subsidizing the farmers and the companies alike in various ways, and of course the companies buy political influence to keep the government doing just that.

One result of this political-economic clusterfuck has been a century of wild overproduction. The US has been paying farmers to reduce production ever since the New Deal, but it has never been able to rein in the overproduction caused by its lavish support of ag input industries. Corn overproduction has been especially perverse, with breeders developing high-fertilizer high-pesticide hybrids at the same time overproduction was surging.

If maximizing profiting from slave labor in the 17th and 18th centuries led to English tea time, profiting from excess corn in the 20th led to farmer payoffs, HFCS, hellish feedlots, ethanol laced gas, and other regrettables. The Omnivore’s Dilemma does a great job explaining what has unfolded since WW2, but those developments were all set up by the much deeper history. The Agricultural Dilemma shows how the government gave lavish support to agricultural industries starting in the early 20th century – undermining the more sustainable forms of agriculture that would have fed us just fine.

The point is that hundreds of businesses, laws, political allegiances, rural landscapes, and even the American palate have been shaped by this history for a century now. Our national integration of agriculture is the country’s biggest and most dysfunctional case of path dependence. Bummer that HFCS makes us fat and diabetic, but it’s part of a system that long ago metastasized throughout our economy. Poor RFK, that’s what he’s up against: its deep history.

Don’t get me wrong: RFK is a quack and an asshole. Normally we only become “food for worms” when we die, but RFK’s brain has already been a buffet for pork tapeworms. If we have another epidemic, many may die because of the bug he has up his ass about vaccines. But in his attack on the toxic zeacentric American agrifood industry, I wish him well.

But let’s not hold our breath.

NOTES

1. For more on this, see P. McMichael 2000 Global food politics. In Hungry for profit: the agribusiness threat to farmers, food, and the environment. Magdoff, Foster, and Buttel, eds., pp. 125-143.

It’s unclear if RFK Jr can grasp what a pendejo he is. I can’t get the image out of my mind of him munching Big Macs with Trump before he declared war on the processed food industry.

Right? And he was washing it down with a HCFS-packed Coke.

We know what he was really eating in that situation.