Speaking of overpopulation: I found Oakwood chapel. I was in England in May and I spent a day tracking down this little chapel that played such a fateful role in Western ideas on population and food.

Oakwood (or Okewood) it is absolutely beautiful, in a fairy tale sort of way, sitting on a small hill surrounded by dense woods in the rolling hills of Surrey.

Apart from a few minor modifications, it looks much as it did in 1789 when young Robert Malthus came here for his first job as a priest. It has dark yellow walls, a pointy bell tower, and a sandstone slab roof. The front door is very heavy, very old, and very small.

To understand the importance of the old chapel with the small door we have to back up a bit. Thomas Robert Malthus – he went by Robert or Bob — was born into a wealthy family in Surrey county in 1766. He later went to Cambridge and majored in math, graduating in 1788. With no job on the horizon, he moved back in with his parents in the village of Albury, where he spent his time “socializing, walking, riding, and shooting” (Stapleton 1986:22). He also did some traveling – fortunate for historians, since several letters from his father during this time exist. Bob had a warm relationship with his father, but the letters show they were having the same arguments young people today often have in this situation: Dad was pushing him to get a job, and he was bristling.

But career was not the only source of argument in the Malthus house. Then, as now, college graduates moving back home had to put up with their parents’ opinions, just as they are trying to establish their own voice. Daniel was an avid reader of the writers of the day, especially Enlightenment philosophers like William Godwin and Jean-Jacques Rousseau — optimistic proponents of the perfectibility of society. Young Bob’s convictions began to take shape that year after college, as he was sitting around getting an earful of his father’s opinions and starting to rebel against them.

Bob thought he wanted to be a clergyman, and after a year at home his father pulled strings to get him a job in the church. He would be the priest at the “woodman’s little chapel” at Oakwood, in the hills nine miles from Albury. He would baptize, bury, and give the occasional sermon. Daniel wrote him that “you would find your first beginning extreamly quiet, with very little duty that could be irksome to you” (Pullen 1986:151).

Oakwood may have been only a short ride from his parents’ home in Albury, but it was a very different parish and a surprisingly different world. This was a backwoods, and the congregation was poor. The young Cambridge graduate was taken aback by their dirt-floored hovels and by the people themselves: where Robert was tall, these peasants were small. He described them a few years later in the booklet that would make him famous, Population:

The sons and daughters of peasants will not be found such rosy cherubs in real life as they are described to be in romances. It cannot fail to be remarked by those who live much in the country that the sons of labourers are very apt to be stunted in their growth, and are a long while arriving at maturity. Boys that you would guess to be fourteen or fifteen are, upon inquiry, frequently found to be eighteen or nineteen. And the lads who drive plough, which must certainly be a healthy exercise, are very rarely seen with any appearance of calves to their legs: a circumstance which can only be attributed to a want either of proper or of sufficient nourishment. (Malthus 1798).

The chapel door is so small I had to stoop to go through it. But Malthus’s parishioners would have had no trouble.

And he was right about the nourishment: taking “a long while arriving at maturity” is an excellent indicator of chronic malnourishment. They must have seemed “like a different race from the lads who played cricket at Cambridge,” wrote Malthus’s biographer (James 1979:43).

What Malthus didn’t know was that he was looking at one of the biggest diet gaps in history. Economist John Komlos (2005) had done a comparison of heights in history, finding the height gap between the rich and poor in late 18th Century England to be a remarkable 22 cm (8.7”) – the biggest gap on record. When Malthus was at Oakwood, poor English children were shorter for their age than any other European or North American group Komlos could find data on. Meanwhile, English elites were strikingly tall — only 2.5 cm shorter than today’s US standards. In his first time rubbing shoulders with the poor, it is no surprise that he was struck by how small they seemed: he was on the winning side of one of the world’s biggest food inequalities.

Life at Oakwood seems to have been every bit as jarring as Paul Ehrlich’s wild ride in a Delhi taxi, described in an earlier blog. And just as Ehrlich’s interpretation of the crowded Delhi streets would spark a lifelong obsession with overpopulation, Malthus would draw life-changing conclusions from these people.

Bit players in history can sometimes affect everything that comes after. Think of Isaac Newton’s apple or the finches that caught Charles Darwin’s attention. So it was with this small congregation of short and skinny-legged English peasants, entrusted to this well-nourished novice preacher coming off of a year of post-college idleness and arguing with his father about Enlightenment theories. Perfectable society? Not on your life, thought Bob.

For starters, young Bob eyed their diet and his reaction was harsh. He saw in the undernourished farmers a sense of entitlement. The population lived almost entirely on bread and Malthus saw this as lavish, later writing that

“The labourers of the South of England are so accustomed to eat fine wheaten bread that they will suffer themselves to be half starved before they will submit to live like the Scotch peasants”.1

He also seemed less worried about his parishoners’ grinding poverty than about the danger that someone might try to help them escape it. As far as he could see, increased earnings would be the worst thing for these people; it would only make them lazy, and impoverish the nation. He wrote:

The receipt of five shillings a day, instead of eighteen pence, would make every man fancy himself comparatively rich and able to indulge himself in many hours or days of leisure. This would give a strong and immediate check to productive industry, and, in a short time, not only the nation would be poorer, but the lower classes themselves would be much more distressed than when they received only eighteen pence a day.

The parish register from Spring 1789, when Malthus took up his position at Oakwood. Some of the entries are in Malthus’s hand.

But Malthus’s main impact came from his analysis of why the Oakwood peasants were so poor and underfed. He was not interested in ministering to needs of the poor, but in analyzing the thin calves and dirt floors as evidence of general processes. But what processes?

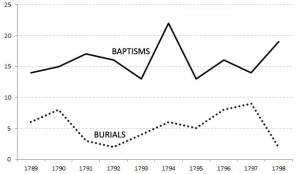

It turned out that Oakwood was in the midst of a tiny population boom during the 1790s. The chapel register for the years 1789-1798 record a yearly rate of 16 baptisms but only 5 burials (Stapleton 1986:27; Surrey Record Society 1927). The Cambridge math major may have computed that at the current rate, local population would quickly explode.

Baptisms and burials at Oakwood Chapel for the 10 years following Malthus’s arrival. Source: Surrey Record Society.

Malthus was clearly thinking of his flock a few years later in Population, even if he does not mention Oakwood by name. They had inspired what Malthus saw as a scientific truth. They are so small because they are underfed; they are underfed because there are too many of them; there are so many of them because they lacked “moral restraint” (a term he introduced in the 2nd edition of Population).

Today demographers can tell you the 16 births a year were a meaningless blip in the curve, and those of us who study food production can tell you that undernourishment almost never coincides with actual food shortages (as dramatized by the situation in India today).

But to the well-nourished elites of the early Industrial Revolution and the owners of the “dark satanic mills,” what could be lovelier than a scientific theory that their workers’ hunger was their own fault. Crime and sickness too. Their reproduction was at fault; it is the way of nature.

This theory, and its various permutations, has proved enormously useful to a wide range of interests in the years since (Ross 1998).

The farmers of Oakwood were well aware that they were small, both physically and economically. But they could have never imagined, as they trudged up the hill every Sunday to sit in the chapel with their hats in their laps, that they would inspire a famous theory that linked their poor diet to their moral failings and even sense of entitlement. We will never know what they thought of the young pastor who towered over them — physically, economically, and — at least in his own mind — morally. Did they have their own theories as to how he had grown so tall, and how he had avoided the hard work that characterized their lives? We don’t know. History is written by the winners, and these people were just small farmers.

I’m not quite sure how to interpret this. Malthus is typically brought up to discredit the notion that human overpopulation will starve itself, while simultaneously there seems to be a universal rationalization from biotech that it will solve the world’s hunger problems. It seems rather obvious that food distribution is not a scientific problem, so I’m not clear on why these arguments are always conflated in this way.

More importantly, overpopulation isn’t simply about the availability of food, but rather the overall impact population growth has in virtually every domain.

It is no coincidence that no demographer imagines human population growth about 11 billion by the end of the century, because there is an implicit assumption that such growth must slow down or produce dire consequences. Yet, it seems that no one wants to address this fundamental problem, instead most prefer to invoke magical thinking that “wealth reduces population” while being somewhat vague on how such wealth is to be produced.

Love it. So that’s where the theory came from.

I had no idea Okewood church was still standing. Do the people there today realize its importance in history?

One of the leaders of the little congregation certainly did, and was proud of it all. Their pamphlet on the chapel’s history mentions it. I don’t know if they are aware of what a political theory it was.

Hi Glenn, just wanted to say that this blog post had a lot of influence on the book manuscript I am trying to finish. All the best, John Walker

Glad to hear it. I’m going back to England soon for research in Malthus’s actual library (which ended up at Jesus College, Cambridge). I hope he was into liner notes.