We have a new E.T.A. on Golden Rice. Well, sort of: the institutes in the Philippines that have been conducting field tests since 2008 say they may be able to submit the needed data for regulatory approval by 2013 in the Philippines and 2015 for Bangla Desh. So maybe a 2014 release in the Philippines.

Golden Rice is genetically modified to produce beta carotene in the grain (instead of just in the bran). It was mainly funded by the Rockefeller Foundation as a possible means of mitigating vitamin A deficiency in Asia, although I think it’s fair to say that Rockefeller has soured a bit on biotech approaches to food improvement since then.

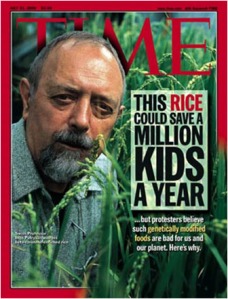

Golden Rice has been the subject of intense promotion since it appeared on the cover of Time in 2000, and many people assume it has been eaten by the poor for years. This illusion has been encouraged by the biotech industry and many others too: for instance, a leading South African biotechnologist who writes on Africa’s food needs scolded the press for “bias” in not covering how it has saved children from blindness, internationally recognized leaders in biotech have claimed Golden Rice to have already saved many lives, and US congressional documents claimed it to have saved the sight of thousands of children..

Golden Rice is still years from being released, but it’s got an even bigger problem: the big ugly M branded on its ass when it was young will cause problems for the rest of its life. It seems that the researchers initially used the 35S promoter to try to get their set of introduced genes to work. A promoter is a stretch of DNA that tells a gene when and where to express. Sometimes a promoter is referred to as a kind of gene, sometimes as a part of the gene, sometimes as something separate from the gene – the terminology isn’t standardized. But they are essential to making genes work, and the most common promoter in genetic research, hands down, is the “Cauliflower Mosaic Virus 35S” promoter — on which Monsanto happens to have a patent. (How anyone can patent naturally occurring DNA anyway? – see my earlier posting, Baseball bats and Breast Cancer.)

DNA patent-holders routinely let researchers use “their” DNA in experiments, but reserve the right to profit from (or block development of) commercial products. In 2000, with an enormous image problem on its hands and meanwhile with Golden Rice on the cover of Time, Monsanto agreed to forego any share of the profits from this rice. It’s doubtful they would have made any money on this crop anyway, especially since the 35S viral promoter was soon replaced with a plant promoter. But for the “altruistic” act of giving up non-existent profits on a rice for the poor, Monsanto launched a shameless PR campaign in which they essentially took credit for actually developing Golden Rice:

They were still crowing about Golden Rice 4 years later, after their promoter had been replaced.

If this was disheartening to Rockefeller, it was infuriating to biotech critics, who up till then had mainly picked fights with commercial products. Their attitude quickly became “If you’re going to clean up your image with Golden Rice, just watch how much mud we can put on Golden Rice.” Golden Rice was a hoax, wrote Vandana Shiva; a trojan, wrote RAFI. Ineffective, said many observers — too little beta carotene to impact health (that was true, but it has greatly improved). Anyway, said Greenpeace, “Why go to the problem of producing golden rice when you still have to eat vegetables anyway?” Some of the attacks were over the top, some had some truth, but many of them wouldn’t have been worth making if not for that big ugly M.

In short, Monsanto obstructed the successful deployment of Golden Rice. (It would have had its detractors anyway, but falsely claiming it to be a corporate product hung a huge and unnecessary target on it.) Monsanto probably further impeded its adoption by publicizing it as a food for the poorest of the poor. Poor people are like everyone else: they don’t want poor people food.

No one knows how Golden Rice will be received in the Philippines. One GM crop (Bt maize) is already being grown there on a small scale but no food crops. GM crops are not a topic of intense debate there as they are in much of Europe and India. Adoption probably won’t be decided on the basis of human health – no one’s going to eat this and suddenly get healthy. It will turn on how the presentation & debate articulate with local culture.

Many people have more or less understood this for some time. Back in 2003, the president of the Philippine Federation of Free Farmers pointed out that the success or failure of Golden Rice all depends on how it is presented to the public; “If we do it carefully and with sensitivity to the concerns of all stakeholders, I think it will be that much easier to sell the technology…But if we do it in an insensitive manner, although it has a lot of promise, it could end up exploding in our faces.”

Many people have more or less understood this for some time. Back in 2003, the president of the Philippine Federation of Free Farmers pointed out that the success or failure of Golden Rice all depends on how it is presented to the public; “If we do it carefully and with sensitivity to the concerns of all stakeholders, I think it will be that much easier to sell the technology…But if we do it in an insensitive manner, although it has a lot of promise, it could end up exploding in our faces.”

And the presentation by its backers is only half the story; if and how anti-GMO forces elect to oppose the rice is the other half. Given how hard it will be to wash off Monsanto’s taint, and given the industry media onslaught we’ll get when it is released, the green activists just might be on it (dare I say) like white on rice.

And that’s just in the Philippines. In Bangla Desh — not to mention India, where it is also being trialed — there will be a shitstorm.

But then why would Potrykus & group use the Monsanto promoter in the first place? It seems like a pretty irresponsible strategy, considering what they were trying to accomplish.

I think Potrykus & group were operating the way non-corporate biologists usually operate. Non-corporate labs aren’t set up to create marketable products; they’re set up for research, and they routinely use patented DNA to get the experiments to work. Lab directors frequently don’t even know the details of the intellectual property encumbrances on genes they are using. They don’t normally have to; for them, the research result is an end in itself, and patent-holders very rarely object to their DNA being used for research. (For microbiology research that is — ecology research is whole different story, and they definitely do block studies of outcrossing and environmental contamination.)

And just about everybody uses 35S.

An exception that proves the rule is the ILTAB lab at the Danforth Plant Science Center. They are an unusual case of a non-corporate research lab that aims to get pro-poor GM crops all the way through the pipeline and into farmers’ fields. And they don’t make a move until they know they are in the clear patent-wise — i.e. they have “freedom to operate.”