Three items crossed my desk this week concerning the factory farm scene, i.e. CAFO’s or Confined Animal Feeding Operations. Two were scientific studies with troubling implications for our health, and one was a dumb piece of clickbait concerning bestiality. Guess which got the press attention.

First the two important ones, both pertaining to, well, shit.

We all know that “shit happens,” but what many people don’t know is how much shit happens to come from factory farms. Some is picked up by the wind; some is sprayed out of giant nozzles. “It’s like it’s raining!” says a neighbor in this video… if you’re in a hurry, go to 2.30. (And sometimes it happens to explode but that’s another story.)

All the particulate matter emanating from CAFO’s is clearly a problem. But now scientists have started looking into just what’s in all this migratory manure. And it’s starting to look like the shit itself is not the biggest worry; it’s what IN the shit.

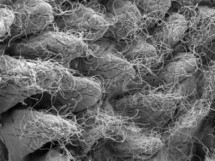

Like genes for antibiotic resistance.

The rise of antibiotic resistant bacterial diseases is one of our most frightening public health problems. This is a medical nightmare with multiple causes, but nontherapeuric antibiotics used just promote growth is emerging as a leading cause. It is also poorly understood: as the authors of a recent review in the microbiology literature put it, efforts to model the impact of nontherapeutic antimicrobials “are thwarted by deficits in key knowledge of microbial and antibiotic loads at each stage of the transmission chain.”

This recent article in Environmental Health Perspectives reports on a study designed to fill in one of those key knowledge gaps:  could CAFO manure in the wind be spreading antibiotic resistance? Environmental toxicologists analyzed particulate matter downwind from 10 cattle CAFO’s in Texas. They found what they were afraid they’d find: the airborne manure was laced with not only antibiotics, but genes for antibiotic resistance.

could CAFO manure in the wind be spreading antibiotic resistance? Environmental toxicologists analyzed particulate matter downwind from 10 cattle CAFO’s in Texas. They found what they were afraid they’d find: the airborne manure was laced with not only antibiotics, but genes for antibiotic resistance.

Their samples were collected very close to the CAFO’s, and they did not study how far these contaminants could travel. But they do cheerfully point out that clouds of dust have been known to travel over 6000 miles, and to carry diseases very long distances.

And like endocrine disrupting chemicals.

We have been busy pumping our environment full of endocrine disruptors, mainly through our food & agriculture systems. They turn boy frogs into girls; they make girls menstruate earlier and boys have smaller testicles; they cause a range of diseases including cancers; they help make us obese (see my earlier post on this). We urgently need to figure out how endocrine disruptors work in the body and how they get into the body.

We have been busy pumping our environment full of endocrine disruptors, mainly through our food & agriculture systems. They turn boy frogs into girls; they make girls menstruate earlier and boys have smaller testicles; they cause a range of diseases including cancers; they help make us obese (see my earlier post on this). We urgently need to figure out how endocrine disruptors work in the body and how they get into the body.

It turns out that cattle in Texas CAFO’s are not only fed nontherapeutic antibiotics to make them grow faster, but also endocrine-disrupting steroids. How does this practice affect public health? This second study of particulate matter blowing from cattle factory farms gives us part of the answer. The same group of environmental toxicology trouble-makers looked at samples of airborne particulate matter from around Texas CAFO’s, finding evidence of synthetic androgen and estradiol. This indicates that “steroids affiliated with feedyard PM have the potential to elicit endocrine-modulating effects.”

The press has shown scant interest in these findings, although it wouldn’t take much journalistic ingenuity to create an attention-grabbing story about the cloud of fecal dust laced with antibiotic resistant genes and endocrine disrupting chemicals wafting from factory farms. They are reserving their attention for more important things…

Which brings us to the third factory farm story for the week, in which a group called Mercy for Animals ran to the press with some reports that factory farm “workers were fondling the genitals of animals” and “making crude sexual remarks” – presumably where the animals could overhear.

Needless to say, this was the story that caught the press’s attention.  It was the one that got the HuffPostLive treatment, complete with a sultry news wench interviewing representatives of the Humane Society and Mercy For Animals.

It was the one that got the HuffPostLive treatment, complete with a sultry news wench interviewing representatives of the Humane Society and Mercy For Animals.

Factory farms are a disgrace, not just for their long list of environmental and public health impacts but for their inexcusable treatment of animals on a massive scale. Life in a CAFO is depicted luridly online and described vividly by Michael Pollan and others. Life is a contaminated hell, and animals have much bigger things to worry about than the occasional handjob from a worker — if this is even happening at all, which I doubt.

The “crude sexual remarks” – (“crude” being superfluous here, unless you know of some sophisticated sexual comments to be made about confined beasts) – have to be even lower on the worry scale. Yes, farm animals can learn some vocabulary. Leadbelly was speaking mule when he wrote “Whoa back buck and gee by the lamb.” Where I work in Andhra Pradesh, the bullocks understand simple Telugu commands like right, left, and stop. But CAFO animals do not understand any of our many terms for genitals. I’m not sure I understand them all myself.

If anyone thinks this is missing the point — that CAFO’s offer a degraded existence for meat animals — then I would say that point is obvious, and is made much more strongly by the many writers and surreptitious videographers who have documented that existence.

We have more serious things to be concerned about than inappropriate touching and talking in the CAFO. Like the bona fide torture of CAFO animals and the public health debacle in the cloud of their shit.

ages to say literally nothing, because anything a farmer does in the operation of a farm is a farming practice. Until farming itself is outlawed, farmers by definition have the right to engage in farming practices. This says nothing about what practices may be regulated; we could pass a law requiring farmers to dress up all their pigs like Porky the Pig and it would be a protected “farming practice” (and a rather festive one at that). Clearly there’s something else going on.

ages to say literally nothing, because anything a farmer does in the operation of a farm is a farming practice. Until farming itself is outlawed, farmers by definition have the right to engage in farming practices. This says nothing about what practices may be regulated; we could pass a law requiring farmers to dress up all their pigs like Porky the Pig and it would be a protected “farming practice” (and a rather festive one at that). Clearly there’s something else going on.

The man behind the wheel, to whom the local extension office had brought me, was great to talk with, no stranger to being photographed, and an able representative of Hachirogata agriculture. He was, of course a show farmer, and last year was even on show for a large delegation of Africans, brought to Japan by the Coalition of African Rice Development working with the Japan International Cooperation Agency.

The man behind the wheel, to whom the local extension office had brought me, was great to talk with, no stranger to being photographed, and an able representative of Hachirogata agriculture. He was, of course a show farmer, and last year was even on show for a large delegation of Africans, brought to Japan by the Coalition of African Rice Development working with the Japan International Cooperation Agency.